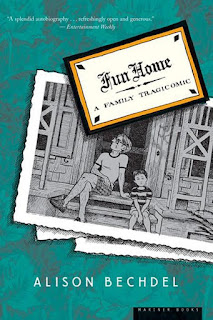

Musical theatre and comics have a strange history together. While some people may remember them fondly, It's a Bird, It's a Plane, It's Superman and Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark are not going to go down in the annals as great American musicals. Comic strips have fared better, producing staples like Annie and You're a Good Man, Charlie Brown, and a few other, less remembered shows, like The Addams Family from a few seasons back. But this past Sunday, the Tony Awards (that's Broadway's answer to the Eisners for those into comics and not into theatre) were held, and a musical based on a graphic novel one four major awards,m including Best Musical. The show was Fun Home, based on the graphic novel of the same name by Alison Bechdel, and while I haven't seen the show yet, I've read the book, and it felt appropriate to write about it today. Now, this is a serious work of autobiography, something more akin to Maus or Persepolis than my usual fair on here, so pardon me if me vocabulary on such weighty topics is a tad more limited than usual.

I'm sure that most of you reading this have heard of Alison Bechdel at some point or another, mostly due to the ubiquitous Bechdel Test. But for a little more context, Bechdel is a cartoonist who started out creating a comic strip called Dykes to Watch Out For (from which the Bechdel Test originated), but broke out to mainstream success in 2006 with Fun Home. Since then, she has released another well regarded memoir, Are You My Mother? and last year was granted a MacCarthur Fellowship, better known popularly as The MacCarthur Genius Grant.

I spend a little more time introducing the creator of the book because Fun Home is a memoir. It's the story of Bechdel's growing up, her maturation, her coming to terms with her own sexuality, and the relationship she had with her father, a closeted gay man who committed suicide when she was twenty. This is heavy stuff, and it's told with a frankness that might make some people uncomfortable; Fun Home is a regularly challenged and banned book for just that reason. But it's also tender and thoughtful, and frankness shouldn't be confused with graphic. Bechdel's book contains very little actual nudity or sex, but she pulls absolutely no punches about the emotional trials she suffered, and those of her father.

As you might imagine, Fun Home isn't the way Bechdel would describe her home life. It's actually what she and her family called the family business, a funeral home. Her father was a funeral director as well as an English teacher, and so Bechdel was raised in a world where death was as commonplace as books. When not working, her father's chief passions seemed to be restoring the century-plus year old house the family lives in. It's through his gardening and restoration we get to know him, how fastidious he was about it, how quick to anger he was by the smallest detail wrong, and how he would smash the beautiful things he loved in the house when something else sparked his anger.

But the book isn't about an angry, abusive father. He would hit his kids, yes, something we now look at as abhorrent, but it wasn't any more than many parents of that generation would (the book takes place mostly in the mid-to-late 60s through 1980), and would fly off the handle in anger, but those weren't his defining characteristics. He was distant. He lived in a world his own, one built on repression of his sexual identity. Bechdel talks about how he seemed to want her to be more feminine because he couldn't be, while she wanted to be more like a boy. These contrasts in their relationship define much of it, although there are occasional, very few, moments where they do connect on a deeper level.

The book is structured in a non-linear manner; this isn't a memoir where in chapter one the writer is born, chapter two she grows up, chapter three she goes to school, etc. Each chapter seems to find it's own theme and purpose, but bits and pieces of story repeat as needed to work with the particular aspect of Bechdel's life. It allows the reader to take in aspects of the story in a different way. There is no chock that Bechdel's father killed himself. It's presented up front, and when it's discussed, the reader can let Bechdel's prose and her art sweep you into the story and her emotions.

Bechdel presents herself in as unvarnished a light as her parents, brothers, and the other people she meets. We watch as she realizes in college that she is a lesbian, although she admits and makes clear that she always felt something was there, even if she didn't have the words for it. That struggle is poignant for anyone who has ever had questions about their own identity, be it sexual or just personal. We also see her struggle with OCD, something I know all too well and immediately latched on to. The chapter where she describes her compulsive journaling and the various obsessive rituals she had to go through every day to make the world seem safe is one of the best descriptions of what OCD can do to you I've ever read.

One of the most interesting aspects of the book to me was how Bechdel used literature to explore the characters. Bechdel's father was an English teacher with shelf upon shelf of lovely old books (something I can also completely relate to), and so books were central to his life. Shortly before he died he began reading Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time (or A Remembrance of Things Past if you prefer the original translated title), and she sees a lot of her father in Proust. She also discusses his fascination with F. Scott Fitzgerald, and how it played into her parents' courtship. She talks about her mother in relation to Henry James's A Portrait of a Lady, and about her time acting in The Importance of Being Earnest, and how Oscar Wilde's trial for gross indecency paralleled her father getting in arrested for an encounter with a young man. And in the final chapter, with Alison away at school, we see her father try to create a meeting of the minds with her through the books she was reading for an English class.

One of the anecdotes in the book involves a young Bechdel coloring in a Wind in the Willows coloring book, and her father getting involved because the colors didn't match those in the novel. Bechdel says that this was the last time colored anything, and so it's interesting to see the style of art used. The book isn't black and white, but is instead black-white-and shades of blue. The extra shades allow for all sorts of gradation in light you can't get with just black and white, and adds an extra aesthetic touch. There are a couple times where Bechdel calls her own memories and experiences trite, as if her memories have been shaded by popular thought, and I wonder if she also used blue as the extra color as it is the color of sadness and loss, the things that permeated her father's life. The art is in general crisp and clear, something important in work that is meant to move beyond the usual bounds of comics fandom. A general audience can easily pick up the book, follow the panel structure and understand what Bechdel is producing.

There's a lot more to dive into with a work like Fun Home. So much of it is character, is the haunted looks of Bechdel's mother, a fascinating character who lives with her husband's infidelities and is as distant from her family as he is. Stories of family vacations are tinged with the memory that many were attended by young men who were her father's assistants and that he desired. And there are questions. Questions of how her father's life might have been different in a different time or place, how he might have been reaching out in the awkward way he could. And the question of whether his death was indeed suicide or an accident (Bechdel clearly feels it was the former, but does not discount the latter), comes up over and over. As with many memoirs, the things you take away from them are often most attached to the things you come in with. And like with most great memoirs, you'll take something back out with you, a little bit of understanding of someone else.

Fun Home is available at all major bookstores and many comic book shops.

No comments:

Post a Comment